So, you all know what a horcrux is — in Slughorn’s words, “an object in which a person has concealed a part of their soul. […] You split your soul, you see […], and hide part of it in an object outside your body. Then, even if one’s body is attacked or destroyed, one cannot die, for part of the soul remains earthbound and undamaged” [1].

There’s a long tradition of the external soul in folktales, and I’ll come back to that in a little while, but first, consider an episode in Taran Wanderer (1967), the fourth book in Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain Chronicles. This is a series, like Harry Potter, that I’ve read many times, and as I said, I made this connection between them some years ago. I can’t remember exactly when now, but I’m guessing it was 2009, or perhaps even a year or two before that.

Without going over the plot of the entire novel (for which, see here), let’s get right to the episode in question (spoilers, obviously!). In a nutshell: Taran and his companions encounter Morda, an evil wizard who has separated his soul from his body and placed it into a small shard of bone, his own severed pinky bone, in fact. With his soul elsewhere, the wizard is now as strong as death and cannot be killed like a mortal man. But as luck (or providence) would have it, Taran has come across this bone. To save the lives of his companions and himself, he tries to snap the bone in half. He can’t do it, but in Morda’s struggle to regain the bone, it does indeed snap and Morda is undone. It’s a memorable scene in a great novel for young people.

Now let’s take a closer look at some of the details here. Apologies if this is a bit lengthy, but there are a number of points I want to call your attention to.

Taran and friends find a small iron coffer, bound in iron bands, and padlocked. Rather recklessly, they break into the coffer, finding a leather pouch containing “a slender piece of bone as long as Taran’s little finger” [2]. Taran’s companion, Fflewddur Fflam, is all for getting rid of it as a dangerous enchantment — quite sensibly. They return it to the coffer, and return that to the hiding place where it was hidden in a hollow tree. But a few pages later, it turns out that Taran’s pet crow, Kaw, has retrieved it, magpie-like, and brought it back to Taran for a prank. Fearing to toss it away now, Taran pockets it. Meanwhile, the companions come upon their friend Doli, who has been transformed into a frog by Morda and left to die.

Eiddileg, King of the Fair Folk, sent to Doli to investigate the theft of one of their treasure troves, and when he was discovered, Morda cast a spell on the dwarf to get rid of him. Casting an enchantment on the Fair Folk was a thing completely unheard of, for which Doli calls “the foul villain of a wizard […] shrewder than a serpent” — the choice to transform Doli into a frog might be relevant here, as frogs are serpent’s prey. Morda mocked him and “savored [his] lingering agony more than the mercy of killing him out of hand” [3].

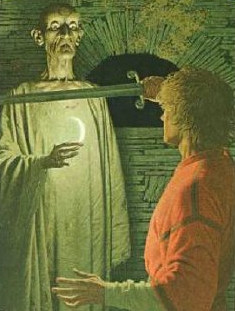

Seeing no other way to reverse the enchantment cast against Doli, Taran, with Gurgi and Kaw, decides to confront Morda. Morda’s dwelling is surrounded by a great wall of thorns, and Kaw is ensnared seeking a way around or over. Taran and Gurgi attempt to climb the wall, but they too are captured, and Fflewddur likewise, not long after. Morda has “a gaunt face the color of dry clay, eyes glittering like cold crystals, deep set in a jutting brow as though at the bottom of a well. The skull was hairless, the mouth a livid scar stitched with wrinkles.” “Morda’s gaze was unblinking. Even in the candle flame the shriveled eyelids never closed […].” His voice is likened to the hiss of a serpent, and “[t]he glint in Morda’s lidless eyes flickered like a serpent’s tongue.” With a magical ornament that he stole, a gem of great power, Morda transforms Fflewddur and Gurgi into a rabbit and a mouse respectively (note: also serpent’s prey), finally rounding on Taran, who “stared at the ornament like a bird fascinated by a serpent.” Later, as they struggle, “the wizard’s relentless grip tightened,” much like a python’s.

Gurgi, in mouse form, gnaws loose the ropes binding Taran. Freed, Taran runs Morda through with his sword — to absolutely no avail whatsoever. But then Taran sees that Morda is missing a finger, and he realizes that this is the very bone he pocketed. Morda has already revealed he had been seeking ways to extend his life. This is the reason he plundered the Fair Folk’s trove, searching for gemstones to lengthen his life beyond “any mortal’s mayfly span of days.” With Angharad’s magical ornament he has learned even to cheat death. “My life is not prisoned in my body. No, it is far from here, beyond the reach of death itself!” he says to Taran. “I have drawn out my very life, hidden it safely where none shall ever find it. Would you slay me? Your hope is useless as the sword you hold.”

Morda attempts to transform Taran, but surprisingly, the spell fails. Taran is not enchanted; something is blocking the spell. Taran has realized the value of the little bone Kaw brought back to him, and Morda has realized that Taran holds his life in his hands. In the ensuing struggle, the bone is finally snapped in two, and “[w]ith a horrible scream that stabbed through the chamber, Morda toppled backward, stiffened, clawed the air, then fell to the ground like a pile of broken twigs.”

Whew! That ran on a bit, didn’t it? But I wanted to point out some important features of this episode. First, and perhaps most obvious is the strong similarity between the finger bone containing Morda’s soul, protecting him from death, and Voldemort’s horcruxes, each serving the same purpose. None of Voldemort’s horcruxes are parts of himself, though you might remember that when the younger Barty Crouch kills his father, “I Transfigured my father’s body. He became a bone … I buried it while wearing the Invisibility Cloak, in the freshly dug earth in front of Hagrid’s cabin” [4]. An incidental similarity, but an interesting one. Another similarity of this same sort and from the same installment of Harry Potter: Morda sacrifices a finger in his quest for immorality much as Pettigrew sacrifices a hand to serve’s Voldemort’s; and likewise, another of the ingredient’s in Voldemort’s return is a bone of his father, straight from his grave.

There is also the significant amount of ophidian imagery shared by Morda and Voldemort, much of which I’ve highlighted above. Both characters are frequently compared to snakes (more so than to anything else), both have unblinking eyes and other features like a serpent, both speak in a hiss.

Along with their occupations (unstoppable evil wizards), their names are quite similar too. I’ve written about the name Voldemort before (you can read that here). Morda clearly reveals the same root, the Latin mors “death”. In his Author’s Note, Lloyd Alexander refers to him as “deathlike”, offering as good a gloss of the name as we need! Oh and did I say unstoppable? In both cases, Voldemort and Morda are respectively stymied in their attempts to curse the protagonist of the story. Harry is protected by Lily’s love and becomes part-horcrux himself; and because he is part-horcrux, it is that horcrux that Voldemort destroys — not Harry himself — with the Avada Kedavra curse during the Battle of Hogwarts. Not unlike the way Taran is protected because he holds Morda’s life in his hands. Morda is also described as “gaunt”, and Potter fans need no reminder that the same word has great significance for Voldemort too.

So, quite similar in many way, yes? But none of this is to suggest Rowling got the idea of horcruxes from Lloyd Alexander! I have no idea whether she’s ever read his work, and in any case, Alexander himself notes in his Author’s Note to Taran Wanderer that “Morda’s life secret […] is familiar in many mythologies.” Rather, both Rowling and Alexander each independently borrowed an idea familiar to them from folklore for their own use.

Tolkien touches on the motif of the external soul in his essay “On Fairy-stories”. Discussing The Monkey’s Heart, a Swahili tale Andrew Lang included in his Lilac Fairy Book, Tolkien writes:

I suspect that its inclusion in a ‘Fairy Book’ is due not primarily to its entertaining quality, but precisely to the monkey’s heart supposed to have been left behind in a bag. That was significant to Lang, the student of folk-lore, even though this curious idea is here used only as a joke; for, in this tale, the monkey’s heart was in fact quite normal and in his breast. None the less this detail is plainly only a secondary use of an ancient and very widespread folk-lore notion, which does occur in fairy-stories;* the notion that the life or strength of a man or creature may reside in some other place or thing; or in some part of the body (especially the heart) that can be detached and hidden in a bag, or under a stone, or in an egg. At one end of recorded folk-lore history this idea was used by George MacDonald in his fairy-story The Giant’s Heart, which derives this central motive (as well as many other details) from well-known traditional tales.This is the same motif seen with Morda’s finger bone and with Voldemort’s horcruxes. I included Tolkien’s footnote in the quotation, because Die Kristallkugel [“The Crystal Ball”] also presents an additional layer of similarity to Lloyd Alexander. In the tale, an enchanter’s power is hidden in an external object, and three brothers confront this wizard attempting to rescue a princess. Two of them have been transformed into animals, an eagle and a whale. All of these motifs resonate closely with the episode in Taran Wanderer.

* [Tolkien’s footnote:] Such as, for instance: The Giant that had no Heart in Dasent’s Popular Tales from the Norse; or The Sea-Maiden in Campbell’s Popular Tales of the West Highlands (no. iv, cf. also no. i); or more remotely Die Kristallkugel in Grimm.

Tolkien goes on to give an even earlier example:

At the other end, indeed in what is probably one of the oldest stories in writing, it occurs in The Tale of the Two Brothers on the Egyptian D’Orsigny [sic; D’Orbiney] papyrus. There the younger brother says to the elder: ‘I shall enchant my heart, and I shall place it upon the top of the flower of the cedar. Now the cedar will be cut down and my heart will fall to the ground, and thou shalt come to seek for it, even though thou pass seven years in seeking it; but when thou has found it, put it into a vase of cold water, and in very truth I shall live.’The motif is once again similar, and this time, the hiding place is a tree, just in in Lloyd Alexander. And of course, in traditional tales of two and three wizard brothers, we hear an echo of Rowling’s “Tale of the Three Brothers” from The Tales of Beedle the Bard. That tale doesn’t make use of the external soul motif directly, but of course, each of the three brothers in the parable seeks to escape or delay death, just as do Voldemort and Morda. And their Deathly Hallows are set up as talismans contrasting directly with Voldemort’s horcruxes.

Another interesting story of this same sort is the Slavic tale of Koschei, included by Andrew Lang in his Red Fairy Book as “The Death of Koschei the Deathless”. Again the tale involves wizards, three of them, not brothers this time, but each married to one of three sisters. Each can transform into a bird of prey, so we have animal transformations once again. Koschei is another enchanter, one who has protected himself from death by hiding his soul inside a needle (rather like Morda’s bone), and that in turn inside an egg, which is inside a duck, inside a hare, locked in an iron chest, which is buried under an oak tree. That is six levels of external protection, just like Voldemort’s six (intentional) horcruxes.

And there are plenty more analogues we might examine! Sir James Frazer surveys the sources rather exhaustively in his mammoth study of magic and religion, The Golden Bough. See Chapter X “The External Soul in Folk-tales” (pp. 95–152) in Volume 11 of the third edition, called Balder the Beautiful: The Fire-Festivals of Europe and the Doctrine of the Eternal Soul, Volume II (published 1913). Frazer finds this motif in the traditional tales of Hindu, Kashmiri, Greek, Italian, Slavic, Lithuanian, German, Scandinavian, Celtic, Egyptian, Arabic, and many other peoples. The basis for their many stories, Frazer argues, was a genuine belief in this principle by primitive peoples.

So Alexander and Rowling are clearly dipping into the same well here, and a very deep one. There is no reason at all to suppose Rowling borrowed from Alexander, and yet the striking similarities between their tales — both dark wizards likened repeatedly to a serpent, both with names meaning “death”, both of whose attempts to curse the protagonist fail — certainly do catch the eye! That these are logical enough characteristics for such a character and could easily occur to authors independently needn’t spoil the fun of dwelling on them. What do you think?

[1] Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. New York: Arthur A. Levine Books [an imprint of Scholastic], 2005, p. 497.

[2] Alexander, Lloyd. Taran Wanderer. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967, p. 91.

[3] Ibid., p. 101–2. Subsequent quotations from Taran Wanderer follow along through this chapter and the next, passim.

[4] Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. New York: Arthur A. Levine Books [an imprint of Scholastic], 2000, p. 690–1.

Perhaps you thought it too obvious to mention, but I'm surprised you didn't at least allude to Sauron and the One Ring. It's a bit further afield than some of the other examples, but I see definite parallels.

ReplyDeleteHi, T. Everett. Yes, certainly, Sauron's Ring is another example of this, at least in a general sense. It's not so much Sauron's soul as a large portion of his power, poured into an artifact that can focus it like a lens on the domination of others. And there are other distinct differences. For example, objects in which the soul is concealed tend to be carefully hidden *away from* their creators. The One Ring differs in that Sauron kept it on his finger and used it until it was taken from him. But they're alike in other ways — e.g., in that their creators' enemies want to destroy these artifacts at any cost.

DeleteBut yes, you're right, it fits this general idea too. It felt a little far afield (as you say) in what was already a longish post, but if I fleshed this out into an article for publication, say, then I'd certainly talk about the One Ring there too.

I have thought for some time that Rowling may be familiar with Alexander, if only due to naming of characters: Dallben\Dumbledore, Gurgi\Hagrid, Taran\Harry (both orphans), Eilonwy\Hermione and Rhun\Ron. And this "horcrux". Certainly it could all be coincidence ... But I stopped admiring her when she took shots at C.S. Lewis, who is both a writing and spiritual hero of mine.

ReplyDelete